Feeling okay about your body as a fat person is difficult and complicated. Writing about it can be even harder, says Melanie Saward, from Queensland University of Technology in this article republished from The Conversation.

When I was a child, the water was a place of freedom. I remember throwing my body around with abandon, revelling in the joy of handstand competitions and long games of mermaids or lifeguards with my sister and cousins.

I’ve swum for most of my life, finding joy in the quiet of the water and the way I can move my body without straining my joints or passing out from trying to exercise in the heat.

But my relationship with the water changed as my body did. To get in the water, to swim, was to strip down to a bathing suit and gave me nowhere to hide. As my breasts grew, hips widened, belly expanded, it got harder and harder to find my freedom in water, unless I was alone.

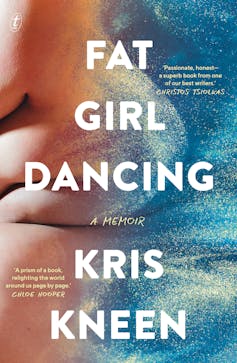

Review: Fat Girl Dancing – Kris Kneen (Text Publishing)

In Kris Kneen’s latest memoir Fat Girl Dancing, they describe a similar freedom in the water and the aloneness they find there:

Sometimes when I am swimming, I feel safe. It is as if the weight I am carrying has been cancelled by the lift of the water. If I’m alone, if there is no one else in the pool to judge me, maybe then I can feel okay about my body.

Feeling okay about your body as a fat person is difficult and complicated. Writing about it can be even harder.

Fat bias

The world is completely biased against fat bodies. Fat people face myriad challenges in their day-to-day life, from the well-documented discrimination on airline travel and public transport, to the size bias from clothing manufacturers. There’s scrutiny over groceries, eating in public, working out, not working out, being visible.

It can be extremely difficult for fat people to access health care where their weight doesn’t become the only thing that doctors focus on. And when they do, tables and blood pressure cuffs and testing machinery are not built with every body in mind. Kneen explores these experiences in her book:

My arm was too big for the cuff. I could tell, but they didn’t seem to notice. I told them it hurt but they just nodded and said it was supposed to be a little uncomfortable. It wasn’t uncomfortable. It hurt, and because it was a machine that repeated the reading on a regular basis it continued to hurt again and again and again.

Thin bodies are held up as the ideal: they are the bodies of social media, movies – and as Kneen (who has written erotic memoirs, fiction and poetry) explores, porn and erotic stories.

Society’s anti-fat bias is so pervading fat people are taught to hate themselves and crave smaller bodies. We fantasise about the thin people shown to us in the media: we have, as Kneen says, become “a part of this system that hates fat women”.

There are also intersections within the fat community, which means that while I consider myself a fat person, I am a straight-sized fat or “a small fat”.

This means I can shop off the rack in many stores, can fit into shoes and chairs, and face less daily scrutiny than many fat folks. I operate in a more privileged subject-positioning: while I face some of the discriminations all fat folks face, I can never understand the full extent of what other, fatter people face.

Understanding is important. And in this memoir, Kneen invites readers into their life and feelings in a way that’s deeply intimate – a way that somehow feels even more intimate than their earlier writing about sex and desire.

Breaking down fatphobia

I’ve been working hard at unpacking my own relationship with my body. I’ve found motivation and understanding in books like What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat by Aubrey Gordon, The Body Is Not An Apology by Sonya Renee Taylor and The F-ck It Diet by Caroline Dooner.

The books I’ve found in the body of fat writing use data and research, coupled with some anecdotes, to break down internal and external fatphobia. But Kneen writes using a mix of forms and structures. Direct essays, where Kneen unpacks an aspect of their life or an experience, are often followed by more “creative” chapters where the writing is more experimental.

Sometimes the reader is pulled right in close to Kneen’s feelings in these sections – and the affect is powerful. Their book does more than just share experiences, it leads the reader through a life: the good, the bad, the complex and the profoundly beautiful.

One of the most beautiful but also disturbing parts of the book is where Kneen goes swimming in Vanuatu and captures the attention of a dugong. Having lost his mate, the male dugong had become a danger to men swimming in the bay. When the dugong appears, he takes a liking to Kneen. At first it’s delightful, but then the dugong pushes them away from the shore. “It was funny and wonderful and terrifying,” Kneen says.

The dugong becomes a repeated motif in the book: why did he take such a liking to Kneen? What would have happened had they allowed themselves to be taken out to sea, to become the dugong’s bride?

I bobbed gently back to the cliff face and climbed up it, grinning, knowing the creature had identified me as something like itself, a great blubbery thing of the ocean. And feeling, for the first time, exactly the right size and shape.

One of the most stunning parts of the book is the way its chapters are punctuated by black-and-white photos of Kneen’s body, taken by their partner Anthony. They’re stunning naked pictures. Kneen says they “hint at the whole of my body without showing which bits we are looking at”.

The intimacy of the book is at its peak here; readers are not just seeing Kneen’s body – invited to look upon it and think about it. We are seeing their body through their partner’s eyes, which is extraordinary. Looking at these pictures, then taking the invitation issued by the book to view the high-resolution versions of the images online, I found myself falling a bit in love with Kneen.

Burlesque is (not) for every body

The book isn’t without its issues, but they’re things I wonder if anyone else would notice. For Kneen, burlesque classes have helped them to be able to look in the mirror and like what they see.

But I am also a dancer in Brisbane and have misgivings about the place where Kneen dances: a place where I found the moves towards diversity and intersectionality felt forced and unnatural, particularly for people of colour. These classes work for some, but not for others.

The cover quotes are from impressive literary names, but no one on the list is fat. And in the mammoth list of follow-up books to read, there are typos an editor who was engaged with the fat community might have noticed.

There’s something interesting about the way Kneen tells their stories about hurt and discrimination. There are moments when they walk into their favourite store, excited to buy a new outfit, only to find the brand has changed patterns and they can’t fit the clothes anymore. There are conversations where well-meaning friends make horrific jokes about their weight, where their mother puts them on a diet.

I worry sometimes, with writing about the fat experience, that incidents like this stir the pities of thin people instead of the sort of empathy we need: empathy that would stir those people to think about how they behave around fat people and the ways they are perpetuating negative stereotypes.

It’s hard for me to say how thin people will read this book. But I think Kneen’s delivery is exquisite and emotionally balanced.

I can see this book creating change, because it is so personal. I found comfort in some of these shared experiences. And I found beauty in the large body – and joy in the way Kneen’s story joins the growing body of books about the fat experience.

Melanie Saward is an Associate Lecturer in Creative Writing at Queensland University of Technology This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.