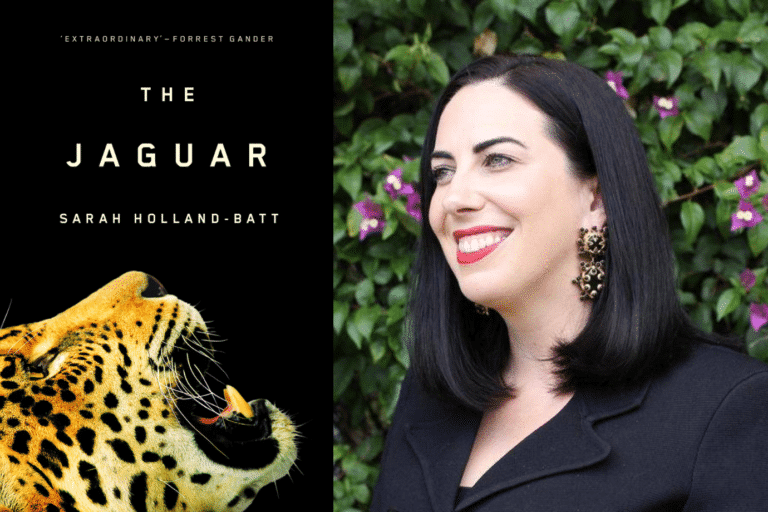

Sarah Holland-Batt’s book, The Jaguar, is an astonishing and lyrical portrait of grief and the relationship she had with her late father, who suffered from Parkinson’s Disease.

She wrote the 2023 Stella Prize winning poetry collection while caring for her dying father and said in response to her win that, “it was the friendship, generosity and camaraderie of women that not only saw me through this difficult time, but has been the sustaining armature of my writing life.”

Speaking with Women’s Agenda, Holland-Batt shares more about how this “camaraderie of women” supported her creative endeavours while she undertook what she considers to be one of the most beautiful and valuable things we can do for another human being: care.

While winning the Stella Prize has been a huge form of “external encouragement”, Holland-Batt notes that many women who are in the middle of their creative careers face “difficulties in balancing caregiving, familial responsibilities and artistic confidence”, and these artists aren’t always given the type of support that prizes like Stella offer.

“There are many women who struggle to maintain that momentum and belief, and I’ve been so lucky,” says Holland-Batt, adding that she’s grateful for the “undocumented network of women supporting one another in the arts and literature,” that she’s found in supportive editors, publishers and fellow writers.

“When you’re a woman with a great group of female friends, there is this incredible net holding you up.”

This sense of community and support from female friends was powerful to Holland-Batt as she continued to write amongst her caregiving responsibilities as well as having to navigate the legalities of a flawed aged care system.

In 2019, Holland-Batt made national headlines when she gave evidence at the aged care royal commission, detailing the neglect and abuse her father suffered in a Queensland nursing home.

Her public advocacy in the aged care system has made big impacts, but she says she didn’t set out to write The Jaguar as a form of direct political activism, as it was a very “intimate and personal” project.

And although her poetry collection sits further in the literary realm than the political, she does hope they “encourage people to see the humanity of an older person, to see the dignity of an older person”, noting that, in this case, “it’s not just any older person, but my father”.

“Most of us who don’t have loved ones in aged care might never visit an aged care facility unless it’s time to go in or time for a parent to go in,” says Holland-Batt.

“To get a sense of the rich inner life that someone with dementia and Parkinson’s still has– the capacity for emotion, the capacity for human feeling— I think that the poems cut through in that sense.”

“They allow people to enter a space that we don’t enter very often.”

She also hopes the book offers consolation to those who are familiar with aged care spaces, and those who carry that personal experience with caregiving.

“So many of the problems that we experience in our aged care system are because of a fundamental lack of empathy and identification with older people,” she says.

“We’re all sad when we hear stories of aged care, but I think many people maintain a kind of insistence that those people are slightly different to us and [think] ‘that’s not going to be me’.”

In order to help change the way that people value caregiving and older people with cognitive or degenerative illness, Holland-Batt tried to throw out the “tired language” around the “burden of caregiving” and replaced it with a sense of beauty throughout her poems.

“Through dad’s illness and through his death and dying, there were many moments of beauty and joy and humour and poignancy that accompanied the sadness,” she says.

Emphasising the nuance and complexity of death and dying, Holland-Batt adds that she wanted these poems to offer a new way of seeing relationships and spaces that are so often portrayed as unrelentingly sad and depressing in television and film.

“I think we have this sort of cultural narrative that a cognitive illness is a death sentence- that we can only feel sadness about it. Somehow the person is almost already dead before they’ve died in that sense, and that was not my experience with dad.”