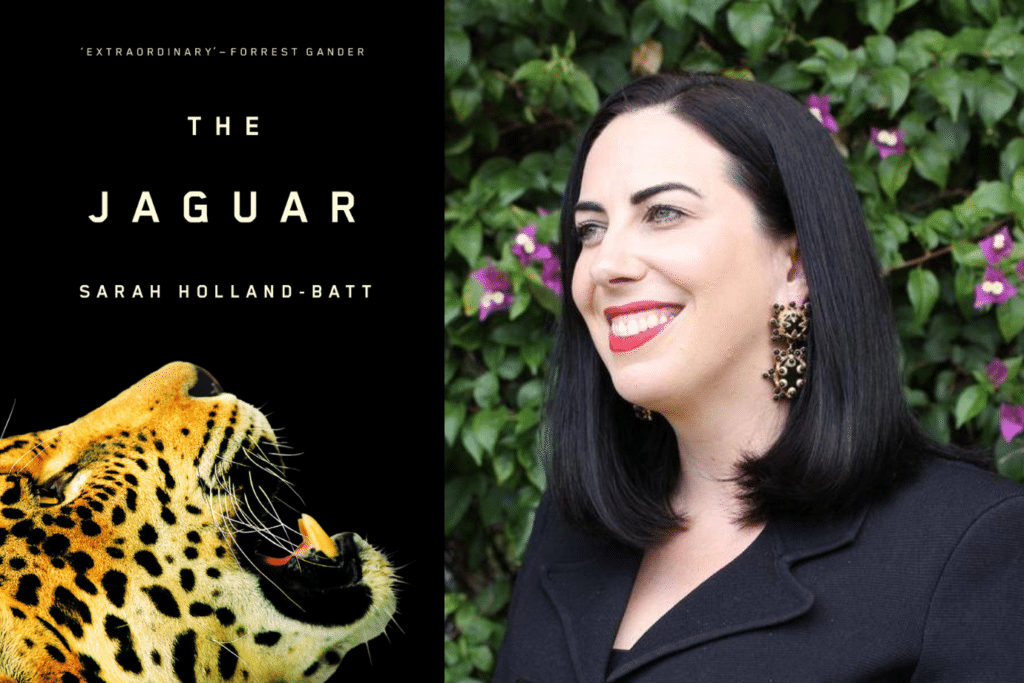

This year’s prestigious Stella Prize for Australian women’s writing has gone to Sarah Holland-Batt and her book, The Jaguar, a poetry collection shaped by the author’s experience with caregiving.

An award-winning poet and Professor of Creative Writing and Literary Studies at QUT, Holland-Batt wrote The Jaguar as she observed and cared for her father’s worsening Parkinson’s Disease.

“My book is an attempt to find the language for that final horizon of our imagining and to think about the act of dying, which we so often resist, yet is the most universal of experiences,” said Holland-Batt, during her acceptance speech at Thursday night’s Stella Prize ceremony.

“Like most women I know, caregiving has been woven throughout the fabric of my working life.”

Awarded annually, the Stella Prize recognises original, excellent and engaging work by Australian women and non-binary writers. In supporting these authors, Stella acts as a voice for gender equality and cultural change in Australian literature.

For winning this year’s Stella Prize, Holland-Batt has also been awarded with $60,000– prize money that has allowed previous year’s winners with the financial opportunity to place more focus on their writing craft.

This is the second consecutive year a book of poetry has won the prestigious award, as last year’s Stella Prize went to Goorie-Koori poet Evelyn Araluen for her debut collection Dropbear.

Holland-Batt said it was “an indescribable joy and deep honour to receive the Stella Prize for The Jaguar”.

“As these poems took place, I found myself wondering more than once whether The Jaguar would be a book that anyone would want to read,” she said. “It’s been moving beyond words to see it’s found the readers it has and to know it’s offered some solace to others who’ve had the privilege of caring for loved ones in old age and vulnerability.”

With the act of caregiving being such a central theme to her poetry collection, Holland-Batt used her acceptance speech to emphasise the vital role carers play in society and how it’s often women taking on this responsibility.

“My father was diagnosed with Parkinson’s the year I turned 18. The drumbeat of specialist appointments, hospital visits and minor and major emergencies was constant across the years,” Holland-Batt said, standing at the podium in Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art.

“Towards the end of his life, when he entered our troubled aged care system, I felt the exigencies of art give way more and more to the exigencies of caring,” she said.

“Among my female friends who are writers and artists, I don’t know a single one who hasn’t felt at some point, the impossibility of fulfilling the duty to care while maintaining an artistic momentum and financial security. And the idea that all three are simultaneously possible is the ultimate illusion women are expected to sustain.”

“This is the context in which women make art,” Holland-Batt said.

“Caregiving is frequently invisible but its consequences radiate out– career breaks, deferred ambitions, missed opportunities.”

“For every book by women that’s published, there are others that idle in the realm of possibility. And I think of this imaginary library often, of the art that might be made were the weight of care on women not so heavy. And yet, I’m mindful here not to use the word burden because it’s the unacknowledged nature of caregiving that is the burden, not the work itself.”

“There is no work more important than caring. No act more valuable than upholding the dignity of another human being. And it’s my profound wish that we might affect a cultural shift in the way we value caring.”