Jesse Tu shares five of her top picks.

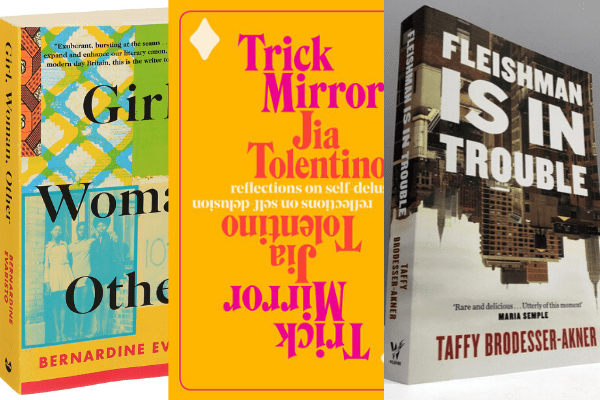

Jia Tolentino: Trick Mirror

In the Introduction to her debut collection of essays, Tolentino writes, ‘I am always confused. I can never be sure of anything.’ Her agent, Amy Williams recently said, ‘If I’m going to trust anyone, it’s someone who’s doubting her own assertions.” In her opening essay, Tolentino considers the effects of social media in engineering identity, public engagement and political integrity. For the New York-based, New Yorker Staff Writer, we are willing participants in a smorgasbord of digital abattoirs, burning through an electronic haze to frantically curate perfect images of ourselves, manifesting the capitalist (and for women, archaic-leaning) ideals of success – the hot-bod, the dewy, plump, snow-white skin. We spend our sporadic income on exfoliating facials and butt masks – ‘coping mechanisms’ for millennials – in search of acceptance.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B3GTTO_FTW2/

This has always seemed odd to me. I’d always used the internet as a way to define myself against the status quo. My rejection of it felt meaningful, triumphant, even. My first boyfriend and I got together because we were the only musicians at a summer music camp who publicly declared our ‘distaste for the online’. Our relationship didn’t last. (Though ironically, a few years later, we would find ourselves on Facebook, exchanging a few messages back and forth, and then, nothing.)

Even so, the internet seems like a good place to start talking about what it means to be a millennial. Most of our lives were assembled around the time of its full gestation: we emerged out of toddler-hood and the pre-teen years just as the internet was springing from the US military’s womb. We have a shared birth, and a kindred life trajectory. And yet, reading Tolentino’s work, it’s hard for the internet to remind me of anything other than the search for ‘mass appeal’, and my natural instinct to turn away from it.

Ann Patchett: The Dutch House

How could one deny oneself the pleasure of plunging into the universe created by this masterful storyteller? This novel has been hailed as Patchett’s finest. Her last book of fiction, Commonwealth was mesmerising in its tenor and characterisation. I found myself often copying whole pages out by hand in my notebook; the sentences are flawless, simple, gracious and never over-cooked.

This latest story centres around Danny and Maeve, a brother and sister pair who are thrust out of their comfort and homes by their step-mother. But it’s not a Disney-fied surface trope of the ‘evil stepmother’ story.

Instead, what she gives us is the spectacular tendency of humans to display humour and rage simultaneously. The power of this book comes from its ability to negotiate the anxieties of her characters, and their acceptance of the “impenetrable mystery” of their father. The best stories are often about the most ordinary things: family love, and the domestic, private lives of our most quiet moments. I found myself drawn to the relationship between the brother and sister more so because rare in literature do we see this relationship examined. This book is a strong, powerful story, and you’ll definitely need to brace yourself with a few slices of cucumber to de-puff your eyes after some cathartic sobbing.

Bernardine Evaristo: Girl, Woman Other

I’ll admit that picking up this book was a bit terrifying. It’s 464 pages long. The average book of fiction is just over 200 pages long. But I was drawn to its alluring, flashy-bold cover. (I always judge a book by its cover)

Immediately, the book draws you in with its lack of traditional grammar and punctuation. I thought I was reading a book of poems. It’s unconventionally structured, with a total of 12 stories, all from women, mostly black, who live in the U.K, across multiple generations. The characters are bold, searing, tender and surprising. There’s a a lesbian socialist playwright, a newly married woman from Barbados, a teacher.

I wanted to hibernate inside their voices. Some were so clear, others, so worked up inside their own confusion and anxieties. I found notions of my history rising up like pieces of dead coral from a vast ocean. This is why we need more writers of colour. I saw myself in some of these characters in a way I’d never had a mirror presented before me. This is what it must feel like to read stories about yourself, narrated, legitimised, celebrated. Regardless of the fact that my ethnicity is not the same as Evaristo’s, I found myself sympathising with Yazz, a young girl whose rebellious attitude and crazy hair reminded me of my teenage self.

Recall that this book and its author were thrust into controversy when it won, alongside Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments, the Booker this year. If you haven’t yet read this one, you really ought to.

Lindy West: The Witches Are Coming

“Trust your instincts. Believe your eyes,” is printed as the epigraph in the beginning of this book.

Lindy West (who penned the brilliant Shrill) has been heralded as an essential (and hilarious) voice for women. This is her second book of non-fiction and it’s no less incisive, sharp and clear as her first, which was made into a highly entertaining (and addictive) series, which was originally showed on Hulu (you can now watch it on SBS Demand).

In The Witches Are Coming, West collates 17 short essays on the topic of the media, and its misogyny and propagandistic-rhetoric that’s spreading like wild fire. There’s sufficient ink devoted to taking down Trump (obviously) and a critical take on the damaging propagation of discriminatory reportage on Muslims and other minority groups.

In an essay titled “Joan”, West begins: “Two ways in which I am a gender traitor… one, I don’t give a shit about pockets on a dress.”

I’ve never read a piece of writing about the merits (rather, de-merits) of pockets on a dress. West later stipulates:

“The feminine directive to love pockets is a cheap simulacrum of gender solidarity where none really exists.”

Ouch. I am a huge fan of pockets on dresses. In fact, they’re the determining factors as to whether I’m purchasing a dress or not.

Taffy Brodesser-Akner: Fleishman is in Trouble

If you haven’t read this book, well, you’re bound to have heard somebody talk about it. Over a period of about two weeks in September, almost ever single person I spoke to (friends, new people, colleagues, etc) had read it, or were in the middle of it. Never have I experienced such a moment of book-ish fever over one novel. It was exciting.

I’d known about Brodesser-Akner from her epic and highly entertaining profile piece on Gwyneth Paltrow’s mega-brand GOOP (for which I am equally repulsed and allured by) and have always believed that feature-writers are, in fact, novelists in the making (or novelists-in-denial: see; Trent Dalton, who is the author of the wildly popular Boy Swallows Universe)

Also, for people generally, if you haven’t read #fleishmanisintrouble yet, lucky, lucky you: joy in store. https://t.co/EMfo2c8p4b

— Nigella Lawson (@Nigella_Lawson) August 17, 2019

I did not tear through this manuscript. The first 1/3 was a slow, shifting meander, as though you’re following a tour guide who’s not quite sure where to take you. But then it zeros into the drama almost like a violent, unperturbed vortex. I didn’t see that coming, but it was welcomed, greatly.

The story is about Toby, a forty-something hepatologist (a doctor who studies the liver, gallbladder, biliary tree, and pancreas). Toby’s wife has just left him, and he’s managing to survive, albeit ungraciously, through the friendship he maintains with his college friend Libby, who used to write articles for a men’s magazine. (Brodesser-Akner herself used to work for GQ). The story is told from her perspective, and it’s her ‘awakening’ to certain oppressions and injustices (almost always hidden, and therefore, somewhat insidious) that the novel picks up steam.

She’s a great writer and has a good handle on sprinkling in the right kind of humour, at the right time. Her writing can at times feel a bit caricature-ish, and sometimes leaks into stream-of-consciousness lucidity. There’s a line that repeats “And yet. And yet. And yet and yet and yet and yet and yet,” almost too many times when the narrator is trying to decide whether or not to sleep with a man.

At the end of the day, it’s an entertaining read, by a wildly gregarious author.

Subscribe to the Women’s Agenda daily update here.