In one way or another, disputes concerning allegations of sexual and domestic abuse usually come down to matters of credibility and believability that play on gendered stereotypes, writes Jessica Lake, from Australian Catholic University, in this article republished from The Conversation.

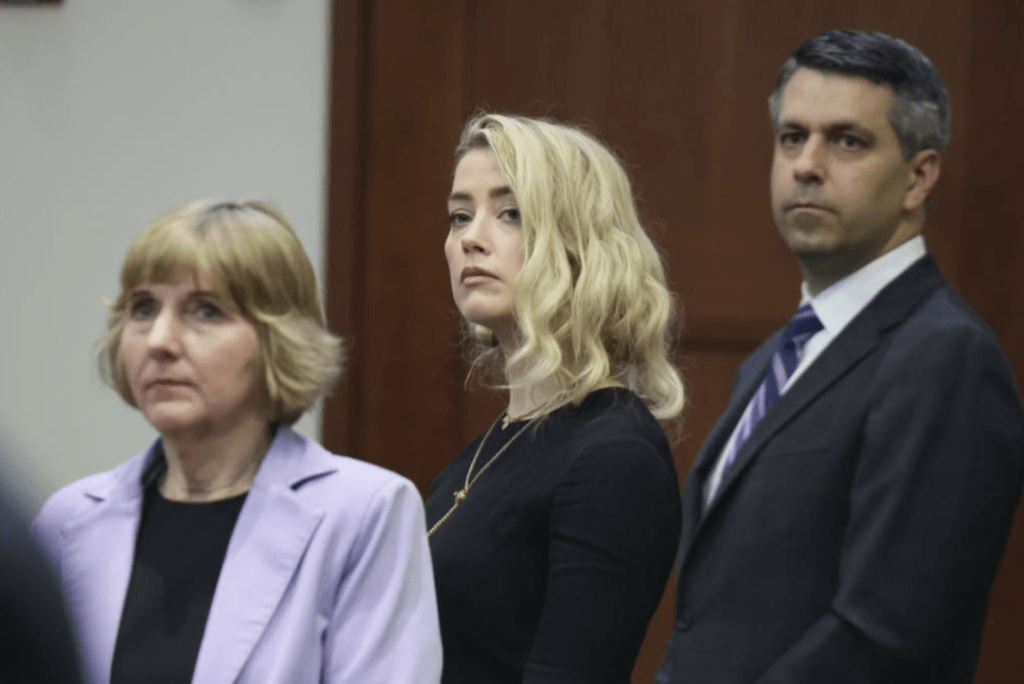

Johnny Depp has won his defamation suit against his ex-wife Amber Heard for her Washington Post op-ed article published in 2018, which stated she was a “public figure representing domestic abuse”.

The facts in every case are unique, and the jury is always in a better position to judge these facts than commentators relying on media reports.

Nevertheless in such a high profile case as this, the verdict has a ripple effect that can go beyond the facts. The unfortunate reality is the Depp Heard case is likely to reinforce the fear that women who come forward with claims of sexual and domestic abuse will encounter a system in which they are unlikely to be believed.

Reform is needed to better balance the protection of men’s individual reputations with the rights of women to speak about their experiences.

Defamation a tool of elite men

Depp was awarded more than US$10 million in damages after convincing the jury Heard was a malicious liar.

This is despite the fact a UK judge determined in 2020 that it was “substantially true” Depp had assaulted Heard repeatedly during their relationship.

After the verdict, Heard commented she was “heartbroken that the mountain of evidence still was not enough to stand up to the disproportionate power, influence, and sway” of her famous ex-husband.

Historically, the common law of defamation was built to protect public men in their professions and trades. It worked to both defend their reputations individually and shut down speech about them as a group.

Data from the United States in the late 20th century shows women comprise only 11% of plaintiffs bringing defamation suits.

As legal scholar Diane Borden has noted, the majority of libel plaintiffs are “men engaged in corporate or public life who boast relatively elite standing in their communities”.

Defamation trials – which run according to complex and idiosyncratic rules – are often lengthy and expensive, thus favouring those with the resources to instigate and pursue them.

Various defences exist, including arguing that the comments are factually true, or that they were made on occasions of “qualified privilege”, where a person has a duty to communicate information and the recipient has a corresponding interest in receiving it.

But in one way or another, disputes concerning allegations of sexual and domestic abuse usually come down to matters of credibility and believability that play on gendered stereotypes.

It becomes another version of “he said, she said”, and as we’ve seen from the social media response to Amber Heard, women making these types of allegations are often positioned as vengeful or malicious liars before their cases even reach the courts. This is despite the fact sexual assault and intimate partner violence are common, and false reporting is rare.

In fact, most victims don’t tell the police, their employer or others what happened to them due to fears of not being believed, facing professional consequences, or being subject to shaming and further abuse.

Heard has received thousands of death threats and suffered relentless mockery on social media.

Time for reform

The global #MeToo movement and recent Australian campaigns, such as those instigated by Grace Tame and Brittany Higgins, encourage survivors to speak out and push collectively for change.

But now, ruinous and humiliating defamation suits could further coerce and convince women to keeping their experiences quiet and private. Measures must be taken to better protect public speech on such matters.

One potential way forward is for defamation trials involving imputations of gendered abuse to incorporate expert evidence about the nature of sexual and domestic violence in our society.

For decades, feminist legal scholars fought for the inclusion of such evidence in criminal trials, especially those relating to matters of self-defence in domestic homicides and issues of consent in rape proceedings.

Expert sociological and psychological evidence can combat and discredit ingrained patriarchal assumptions and myths – comments and questions such as “what was she wearing?”; “why didn’t she fight back?”; “why didn’t she just leave him?”; “why was she nice to him afterwards?” or “why didn’t she tell people at the time?”

Otherwise, pervasive gender bias – often held by both men and women, judge and jury – can undermine the voices and accounts of women before they even set foot in court, before they even open their mouths.

Defamation trials have not traditionally included such expert evidence. But now that they have become a powerful forum for silencing speech about gendered harm, perhaps it’s time they did so.

Jessica Lake, Research Fellow, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.